A New Food Pyramid, a New Direction: What the Latest U.S. Dietary Guidelines Really Mean

For decades, dietary guidelines have been a source of confusion, contradiction, and quiet frustration. Every five years, the pyramid changes shape, food groups move up or down, and the public is told—once again—that this time the science is settled.

Now, under the administration of Donald Trump, a new set of U.S. dietary guidelines has been released, closely aligned with the “Make America Healthy Again” (MAHA) agenda championed by Robert F. Kennedy Jr..

And for the first time in a long time, the conversation is shifting in a direction that deserves serious attention.

What’s Changed in the New Guidelines

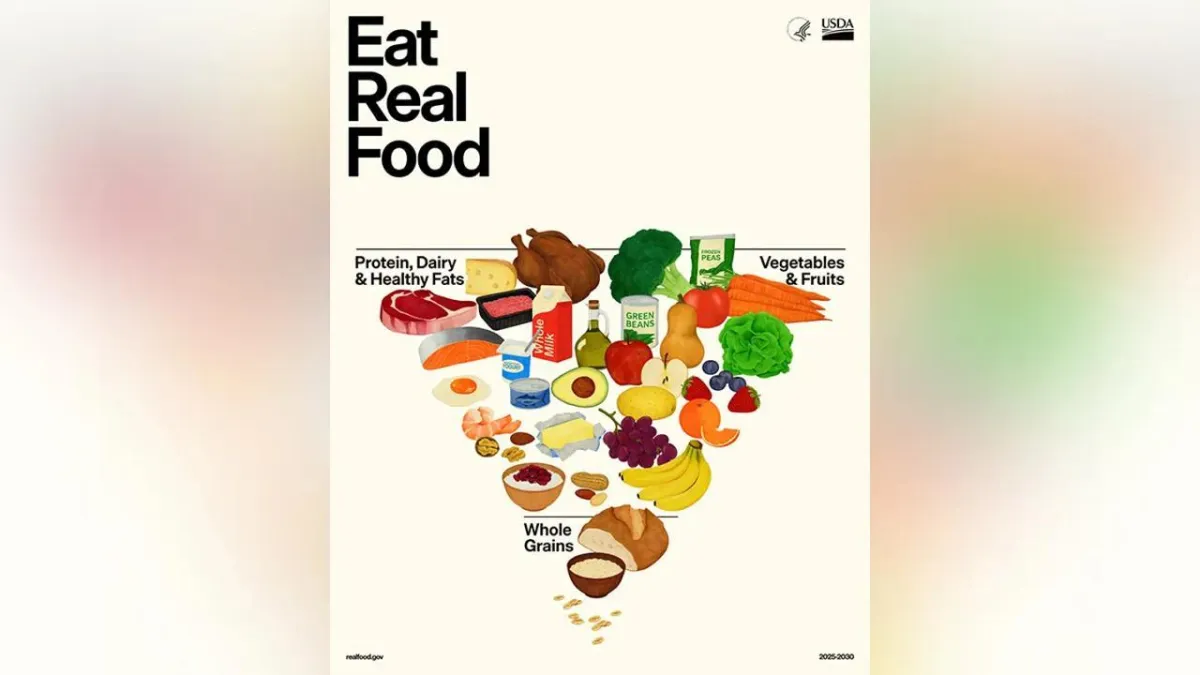

The updated guidelines—issued jointly by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services—recommend:

More protein, with adult intake increased to 1.2–1.6 grams per kilogram of body weight, up from the long-standing 0.8 g/kg recommendation

Less sugar, with a strong discouragement of added sugars

Avoidance of highly processed foods, artificial flavours, dyes, and preservatives

Whole, nutrient-dense foods as the foundation of a healthy diet

In a notable departure from past messaging, the guidelines state plainly that:

“No amount of added sugars or non-nutritive sweeteners is recommended or considered part of a healthy or nutritious diet.”

That sentence alone represents a significant philosophical shift.

Why Protein Is Finally Being Taken Seriously

For years, protein has been quietly underplayed in official dietary advice, despite its central role in:

Muscle maintenance

Metabolic rate

Blood sugar control

Satiety and appetite regulation

The new protein targets align far more closely with what we see in real-world physiology, aging research, and metabolic health outcomes.

This change alone has the potential to:

Improve body composition

Reduce frailty in older adults

Lower cravings driven by under-nutrition

The Sugar Line in the Sand

Perhaps the most symbolic moment came when Kennedy declared:

“Today, our government declares war on added sugar.”

For decades, guidelines allowed sugar to be added “in small amounts” to make healthier foods more palatable—as long as it stayed under a percentage of daily calories.

That logic is now being abandoned.

Added sugars are no longer framed as a tolerable compromise, but as a net negative that fuels obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic dysfunction.

A Quiet Reversal on Full-Fat Dairy

Another meaningful shift: the guidelines now encourage full-fat dairy, reversing decades of advice that pushed low-fat and fat-free options.

This matters because:

Full-fat dairy is more satiating

Fat-soluble vitamins require fat for absorption

Ultra-processed low-fat alternatives often contain added sugars and stabilisers

Dairy farmers have long argued that low-fat guidance harmed both public health and agricultural sustainability. This change suggests that argument is finally being heard.

Alcohol: Less Spin, More Honesty

The long-standing recommendation to limit alcohol to one or two drinks per day has been removed. Instead, the guidance simply states that:

Adults should consume less alcohol for better overall health.

It’s not dramatic—but it’s more honest.

What Didn’t Change (And Why That Matters)

Some familiar recommendations remain:

Emphasis on fruits and vegetables

Continued inclusion of whole grains

Saturated fat capped at 10% of calories

These elements signal that the shift is evolutionary rather than revolutionary.

But the tone has changed—and tone matters.

Ultra-Processed Foods: The Elephant Still in the Room

Interestingly, the guidelines do not yet define ultra-processed foods, despite widespread global research linking them to poor health outcomes.

That omission is acknowledged.

Both HHS and USDA have confirmed that a federal definition of ultra-processed foods is in development—a move that could have major implications for food labelling, school meals, and consumer awareness.

Scientists worldwide have repeatedly shown that ultra-processed foods—rich in additives, industrial oils, and engineered ingredients—are strongly associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and chronic disease.

If and when a formal definition is adopted, the ripple effects will be substantial.

Why This Matters Beyond Nutrition

These guidelines shape:

School meals for nearly 30 million children

Federal nutrition programs

Medical advice

Public health messaging

Food industry reformulation

They also sit at the intersection of healthcare costs and political pressure. Rising chronic disease rates are unsustainable, and both parties know it.

As Kennedy put it:

“Whole, nutrient-dense food is the most effective path to better health and lower healthcare costs.”

On that point, it’s hard to argue.

The Bigger Picture

This isn’t about left or right.

It isn’t about ideology.

It’s about acknowledging something increasingly obvious:

A food system built for scale, shelf life, and profit cannot be the foundation of human health.

The new guidelines don’t solve everything—but they mark a clear step away from denial.

And that alone makes them worth paying attention to.

If nothing else, this update confirms what many people have already learned the hard way:

Real food still matters. Protein matters. Sugar isn’t harmless. And ultra-processing has a cost.

The question now is whether policy, industry, and public behaviour will follow the science—or continue to lag behind it.